In The Wizard of Oz, Things Aren’t Always What They Appear To Be…

It’s fairly easy to see the parallels between the fire-breathing huckster known as The Great and Powerful Oz and the 45th president of the United States. There’s the hulking projected head. The bellowing voice and menacing talk from behind the stage curtain. The glittering trappings of regal luxury. The obedient and unbending military guards. The absent wife. The weighty proclamations. And of course, the jewel of a city — a nation locked inside an impenetrable towering wall — a necessity in times of upheaval, threat or perceived siege. The Wizard of Oz, like every good showman has his bag of tricks, his signature skills of stage craft. With political leaders, they have an added benefit. A devout party of followers who unwittingly conspire with the showman to sell his sleight-of-hand magic trick.

For the larger captive audience, unwilling to go along with the sleep-inducing magic trick, a strong independent voice shouting from the back of the auditorium is needed to shake the slumbering masses and call out the trickster’s hoax for what it is, a wizard’s illusion.

Dorothy is Ruby Red Mad!

Dorothy Gale, the tenacious protagonist of L. Frank Baum’s, The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, is the small town every-girl who pulls back the curtain on the lie that is, Oz.

Universally acknowledged as one of the earliest feminist characters in American children’s literature, it is Dorothy who symbolically awakens the local citizenry and her fellow slumbering travelers. And it is Dorothy’s fearless independent character that compels her to question her surroundings and predicament in life. Through Dorothy’s problem-solving skills and determined leadership the ragtag troupe eventually extinguishes the evil that is nipping at Dorothy’s ruby red heels. There is no need or instinctual desire for external rescue. Dorothy operates on her own free will.

The feminist catalyst is what makes The Wonderful Wizard of Oz such a prophetic and poignant political analogy for today. Particularly for those now living under a turbulent Trumpian rule. But fortunately for the disaffected, as main streets and town squares across the country fill with protestors marching for their voices to be heard and counted by the new administration — we are witnessing the awakening of hundreds of thousands of Dorothy Gales. A growing contingent of newly realized activists who’ve tossed their ruby shoes and replaced them with ruby hats.

Waltzing with Matilda

L. Frank Baum and his wife, Maud (Gage) Baum in Egypt, 1906

L. Frank Baum was the son of privilege. He was raised at the family estate, Rose Lawn, a gabled home surrounded by lush green lawns and flower gardens in upstate New York. Baum was tutored at Rose Lawn and recounted his time there as “idyllic”. During his youth Baum was described as handsome, imaginative and charming. But, he was saddled with a rheumatic heart that guided the young man towards reading, writing and daydreaming — avoiding more muscular pursuits. Perhaps for this reason, Baum, rather than follow his wealthy father’s footsteps and become a businessman chose to follow his passion, the path of an artist. The young idealistic Baum wrote and acted in several plays during his twenties, with his aunt starring in his productions, in the theater Baum’s father built for him.

In 1882, Baum the aspiring playwright fell in love and married Maud Gage, a headstrong college student. Baum considered Maud his equal. She was described as having “dark hair, a shapely figure, and eyes as sharp as her mind”. Maud was also the daughter of the free thinker and activist, Matilda Electa Joslyn Gage. Matilda became an influential figure in the Gage-Baum home.

Real Life Inspiration

Shrewd and perceptive, Matilda initially opposed her daughter’s choice for a husband. She did not want her bright young daughter, a student at Cornell University, to abandon her studies to marry the handsome “impractical dreamer”. When Maud threatened to elope, Matilda realized that her daughter’s will was as strong as her own, so the indomitable Matilda relented. Over time, Matilda was won over by Baum and her position softened. The extended family eventually bonded over mutual respect and shared ideology with Baum commenting that his mother-in-law was perhaps, “the most gifted and educated woman of her age”.

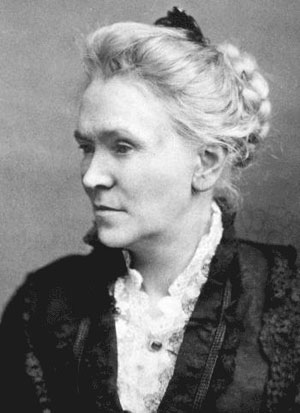

Essentially forgotten by modern historians, Maud’s mother, Matilda, was a well-known activist in her time. She was a suffragist, a Native American rights activist, an abolitionist, a freethinker, and a prolific author, who was “born with a hatred of oppression”. Matilda Gage came from a family of steadfast abolitionists. They lived in a station house — a linked series of abolitionist homes that sheltered runaway slaves during their journey North on the underground railroad. Matilda risked lengthy prison sentences for providing runaways a safe haven.

Matilda Electa Joslyn Gage — mother of Maud Gage and L. Frank Baum’s mother-in-law.

During her lifetime of activism, Matilda was considered to be more radical than her colleagues, Susan B. Anthony or Elizabeth Cady Stanton. Matilda, along with Stanton, was a vocal critic of the patriarchal influence inherent in the Christian Church. She believed that women deserved the right to vote not simply as a means to influence legislation with a feminine Christian morality (as others did) but as the ‘natural right’ of a human being. She believed that matriarchy had been suppressed throughout history and that women had been devalued, dehumanized and demonized as witches.

Matilda Gage also practiced theosophy — an esoteric philosophy that seeks to understand the mysteries, origins, and purpose of the universe. Matilda is credited with introducing Maud and Frank to theosophy. In 1890, Baum wrote a series of articles praising the Theosophy movement. In 1892, after the family moved from South Dakota to Illinois, Baum joined the Theosophical Society of Chicago. Thomas Alva Edison, a contemporary, was a also a practitioner of theosophy.

Dorothy’s Character

Given Baum’s admiration, shared philosophies and close relationship with his mother-in-law, one can safely speculate that Baum based the character of Dorothy on Matilda. Baum’s Dorothy character so strikingly departs from the passive female characters found in traditional literature of the time that ‘real life’ inspiration surely played a large role in Dorothy’s character creation.

Baum’s Dorothy is independent, an optimist, someone who relies on her intellect and problem solving skills to make her way. Dorothy is also, by her own grace and determination the de facto leader of her ragtag troupe in Oz. As the leader, Dorothy helps her peers (who happen to be all male) and the strangers she meets on her journey. All of Dorothy’s character traits and ideals hew closely to the real character of Matilda Gage.

Maud, We’re Not in Kansas Anymore

After a series of misadventures as a struggling actor and playwright in his home state of New York, Baum and his new wife Maud decided to move their young family to Aberdeen, South Dakota. The tipping point for the couple was a devastating fire at the family owned Richburg theater during a production of Baum’s ironically titled drama, Matches. The 1888 move from the East Coast to the Midwest was at Maud’s suggestion. Moving to Aberdeen would allow the young mother to be closer to her brother and sisters while recovering from life-threatening complications brought on during the birth of her second son.

Once in Aberdeen, the ever-optimistic and entrepreneurial Baum opened a store called “Baum’s Bazaar” — a unique housewares and novelty shop. Within a year the store was in the red. In part due to the faltering local economy — a slump triggered by recent tornadoes, drought and a failed wheat crop. But the store’s demise was also likely due to Baum’s soft-hearted business skills which included the habit of selling store goods on credit. In a little over a year, Baum’s quirky little shop went bankrupt and Baum was forced, once again, to search for another occupation and means to support his growing family.

The Landlady and the Newspaper

Aberdeen, South Dakota – Late 1800s.

At the start of 1890, shortly after the store bankruptcy, Baum had just enough money to purchase a weekly newspaper, The Dakota Pioneer, from John H. Drake, an old acquaintance from Syracuse, New York. His finances limited, Baum completed the purchase of the newspaper in monthly installments. He renamed his bold acquisition, The Aberdeen Saturday Pioneer, publishing his first issue in January 1890. His duties as publisher included not only writing and typesetting the newspaper, but also selling subscriptions and advertising. Baum supplemented his hard earned income with miscellaneous printing jobs when possible.

The Aberdeen Saturday Pioneer covered a wide range of subjects. The most popular column in Baum’s newspaper was called, Our Landlady. The opinion column appeared in almost every issue of the newspaper. A supporter of the women’s suffrage movement, Baum was known to publish general news articles and commentary supporting the movement. These articles were written in part or (some say) solely by his mother-in-law, the talented writer and suffragette Matilda Joslyn Gage. Baum acknowledged that Matilda, the daughter of abolitionists, was influential in his life and political perspectives. The Our Landlady column was a prime example of her influence.

The lead character the Our Landlady column, Mrs. Sairy Ann Bilkins, is an opinionated, husband-hunting busybody who owns and operates the local boarding house. Mrs. Bilkins is also an uneducated, penny-pinching “bilker” who uses malapropisms and harsh rhetoric to make her point. Baum employed the tools of satire to expose both social and political hypocrisy — using Mrs. Bilkins as both a protagonist and a foil for his own views and opinions — he would “allow” the landlady to disagree for irony or comedic reasons. Within this satirical framework, when the landlady speaks it is more likely than not, that the landlady is speaking from the perspective of and in the blunt voice of “the land lord, or the oppressor”.

The landlady is the perfect mouthpiece for a sarcastic suffragette and her sympathetic son-in-law. Mrs. Bilkins can comfortably poke fun at the ruling system and also those who quietly accept oppressive societal norms for self preservation. The opinionated, double-edged Mrs. Sairy Ann Bilkins is just as likely to skewer women as she is men.

At times, the sharp satirical swings of Baum’s editorial writing make it difficult for readers to determine Baum’s authentic views. And, while we are certain of Baum’s stance on feminism and suffragettes, other political views he expressed through the landlady persona or in his editorials for The Aberdeen Saturday Pioneer have generated controversy and negative backlash. Over the years, many lingering questions about Baum’s politics and views on non-whites, particularly Native Americans, have persisted — ultimately clouding his legacy.

A deeper look into Baum’s upbringing, his relationships and his life’s work offers evidence that his detractors may have gotten it all wrong.

Satire Speaks Even When You Don’t Hear It

When the Mrs. Sairy Ann Bilkins of the Our Landlady speaks, she is speaking from the satirical pulpit of Frank Baum and Matilda Gage. Much like the self-important conservative blowhard created by Stephen Colbert in Comedy Central’s, The Colbert Report.

The Colbert character is an over-the-top right-winger. He is a boorish patriarch, a partisan, and a gleeful, flag-waving champion of war. Colbert’s character is also shamelessly content to be blinded by these bellicose virtues. The Aberdeen landlady speaks with the same shameless arrogance and peppery irony as the fictional Colbert character.

The harshness of the landlady’s (aka Matilda’s) tone can be off-putting, but that is ultimately the point — to shake the reader. When reading the controversial editorials about the oppression and massacre of Indians in The Aberdeen Saturday Pioneer, understanding this satirical dynamic is key to the message. Because the creative mind, the caustic pen behind both the editorials and the Our Landlady column are one in the same. Excerpts from the two most controversial editorials follow:

“The Whites, by law of conquest, by justice of civilization, are masters of the American continent, and the best safety of the frontier settlements will be secured by the total annihilation of the few remaining Indians. Why not annihilation?”

“…our only safety depends upon the total extermination of the Indians. Having wronged them for centuries we had better, in order to protect our civilization, follow it up by one more wrong and wipe these untamed and untamable creatures from the face of the earth.”

Iroquois war dance at Pine Ridge, 1890

These two passages read (on the surface) as racist and as supporting genocide. And that is exactly the writer’s intent, to speak in the voice of the oppressor and shed light on the dark rationalization of these acts. If “conquest” is your law and civilization your “justification”, why should a “master of the American continent” show mercy? It is a stinging rebuke. If you are a truly civilized and law abiding noble man, where is your mercy?

While every form of art is open to interpretation, it should go without saying that an individual advocating (with dark sarcasm) for “one more wrong” is not someone who sees that “wrong” as a right. There is no justification that would make a wrong a right. Through and through, a wrong is a wrong.

It is highly unlikely that Matilda Joslyn Gage, a suffragette, a lifelong abolitionist and Indian rights activist, honored by the Iroquois Indians would allow intolerance or oppression to live in her home or within her family. (Matilda was initiated into the Iroquois Wolf Clan and received the name Karonienhawi which translates to “she who holds the sky”.) Baum, though not a Wolf Clan initiate like his mother-in-law Matilda, likely held similar views on subjugation and intolerance.

Baum’s early stinging satirical editorials evolved into a more subtle style of satire in his later fictional work. His children’s stories display a lyrical ease, and artful finesse with multilayered subtext. From Dorothy’s buoyant and kinetic feminism in The Wonderful Wizard of Oz to the celebration of Native American myths in stories like The Enchanted Buffalo where an imposter is revealed and has his comeuppance. There is a consistency in Baum’s work, which exhibits a level of tolerance and inclusiveness that was unheard of at the turn of the century.

Throughout Baum’s collective writing, threads of sociopolitical satire are woven – illustrating an artist’s mind that is quietly and constantly picking at the lock of social awareness.

Dust Bowl Days and Wizards at the Fair

Chicago World’s Fair – World Columbian Exposition Exhibit Hall By Hemming Hultgren, via Wikimedia Commons

From 1889 to 1890, during Baum’s tenure as the owner and editor of The Aberdeen Saturday Pioneer newspaper, the area around Aberdeen experienced regional economic collapse. The plains of the South Dakota territory were hit by extreme weather, which included: multiple tornadoes, a devastating drought which culminated in a failed wheat crop. All of these environmental factors conspired to drive the South Dakota regional economy into a rapid decline and with the failing economy, went Baum’s fledgling paper, The Aberdeen Saturday Pioneer.

In 1891, desperate and looking for new income opportunities, Baum made plans to move with his wife and their sons from South Dakota to the Humboldt Park section of Chicago, where Baum found a job reporting for the Evening Post. Baum arrived ahead of his family in the windy city where workers were busy building glimmering white towering structures for the Chicago World’s Fair. After the dusty plains of the Dakotas, Chicago may have seemed like the emerald city itself.

His first article for the Evening Post was a front-page article on May 1, 1891, about the experience of relocating. “Many a proud man will sleep on the floor tonight,” he wrote, “for this is moving day. This is the day when man lives as it is written he shall, by the perspiration of his brow. Also is it the day when the wife…whispers in your ear the beauty of the poet’s tip that there is no place like home.” This was the lowest point in Baum’s career with a parade of failed businesses behind him, Baum was now living in what many would call a slum, waiting for his wife and children to arrive. By his own words, Baum found solace and hope in his family joining him and in Theosophy. Inspiration would come from his new surroundings and interestingly enough, his mother-in-law.

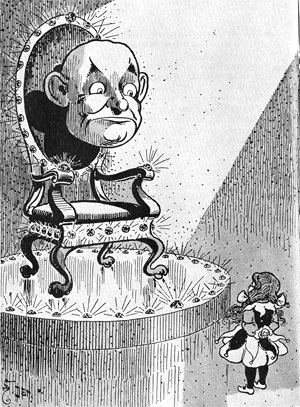

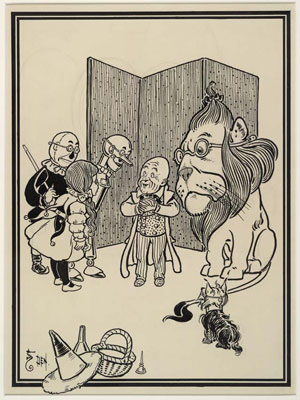

Dorothy and the Wizard’s head — from the book, The Wonderful Wizard of Oz.

Captivated by the technological marvels unveiled at the World’s Fair, Baum expressed special awe at inventor Thomas Alva Edison’s appearance at the fair, where the Wizard of Menlo Park stated, “I hope to be able to throw upon a canvas a perfect picture of anybody and reproduce his words.” Baum described the wizard as having a “A massive head…” foreshadowing his description of Oz in The Wonderful Wizard, who first appears only as “an enormous head, without a body to support it or any arms or legs whatever.”

The world fair and came and went, and so did more careers for the intrepid Baum. One as a china salesman and another as the editor of The Show Window, a magazine focused on store window displays. In his Shop Window magazine, Baum wrote about the fantastic holiday displays created by major department stores using clockwork mechanisms to animate people and animals. For the creative Baum, the store displays became more wondrous turn of century gadgetry inspiration. During this period, Maud and her mother Matilda kept encouraging Baum to write stories. Matilda wrote to Baum, “Now you are a good writer and I advise you to try,” suggesting further, “If you could get up a series of adventures or a Dakota blizzard…or maybe bring in a cyclone from North Dakota.”

Matilda’s fiery spirit and words of encouragement were silenced when she suffered a stroke and died in March 1898, at the age of 72. Shortly after her death, Baum was overwhelmed by a flood of images and ideas that converged during a transcendent moment in the entrance to his Chicago home. “Suddenly, this story came in and took possession,” he exclaimed. “The story really seemed to write itself…” Baum’s new story opened with the vision of a bleak prairie landscape and menacing cyclone.

We’re Off to See the Wizard

The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, First Edition, published in 1900.

In January 1901, the George M. Hill Company completed the first edition print run of 10,000 copies. The initial run quickly sold out. By the time the book entered the public domain in 1956, The Wonderful Wizard of Oz had sold three million copies.

The Wizard of Oz movie followed in 1939. Unlike the children’s book, the movie was not an immediate sensation. Even though film critics of the day may have lauded it as such. The general public was not won over by the adventurous fantasy movie. Early devotees praised Oz for its glorious technicolor, an unforgettable musical score, never-before-seen special effects, eye-catching costumes, dramatic sets, and cast of unusual characters, including everyone’s favorite, the munchkins.

It was MGM’s most expensive production at that time. But, The Wizard of Oz movie did not recoup the studio’s investment, or turn a profit until the theatrical re-releases starting in 1949.

In 1956, CBS television reintroduced the film to the broader TV audience. Watching Oz has now become an annual tradition. It is ingrained in the American consciousness, beloved and an undisputed behemoth of pop culture. Everyone knows the story of Dorothy and her little dog Toto too. Signature Oz phrases, characters and plot lines have all made their way into our modern cultural zeitgeist.

When the Shoe Fits

The Wizard, Dorothy, Tin Woodman, Scarecrow, Lion. From the movie, The Wizard of Oz, 1939.

Over the years, scholars have interpreted The Wizard of Oz through the prism of both politics and religion. While Baum’s family, mentors, and life experience certainly influenced and shape his creative writing, exactly how political was Baum’s children’s book writing? Educator and historian Henry M Littlefield published a highly cited essay in 1964, entitled, The Wizard of Oz: Parable on Populism. Littlefield’s essay interprets Baum’s story as a straightforward political satire, with the characters and landscape of Oz representing distinct political forces. Littlefield pinpoints what he sees as symbols of monetary reform i.e., Dorothy’s silver shoes represent the silver standard, and the yellow brick road represents the gold standard. Scholars and educators quickly adopted Littlefield’s interpretation as a means to breathe dramatic life into political history and economic theories of the period.

Littlefield’s take on political symbolism is intriguing and difficult to dismiss given the influence of the Populist movement in late ninetieth century America. Baum would have witnessed the social unrest of the time as well as the political warfare between the opposing political parties. During the 1896 and 1900 presidential campaigns, changing the monetary standard from gold to silver was a platform pledge of the late ninetieth century Populist movement and a key campaign message of the controversial Democratic presidential nominee, William Jennings Bryan. Many political historians (Littlefield included) see the cowardly lion in the The Wizard of Oz as representing the famous orator and politician, Bryan. The Tin Woodman represents the steel and industrial workers like those in the Carnegie-owned mills of Pittsburgh, who were fighting for better wages and union representation. The Scarecrow, the downtrodden farmers of the Midwest. And Dorothy, represents the American individual, hope and ideals.

Wizard of Oz Movie, Yellow Brick Road Scene.

Still other scholars call into question whether Baum ever intended the story to be satire. Baum himself has adamantly stated that he wrote The Wonderful Wizard of Oz “solely to pleasure the children”. Academics like Quentin Taylor still find enough parallels to argue that the book is a deliberate work of political symbolism.

But is The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, a purely partisan creation with a distinct hardwired political perspective? Was it written as a tool to further a specific political agenda? Or perhaps, is it on the surface a deliberate work of political symbolism — but at its heart, like most fine art, an artist’s very personal sociopolitical commentary? A charming handwritten note to humanity, authored by a theosophist who embraces the enduring power of optimism, American individualism, fellowship and believing in yourself along the journey of life.

Baum’s theosophic storytelling, filled with odd creatures and broken-down characters who journey through wondrous landscapes seems more about misfits and the enduring struggle of “the individual” within confines of society, than it does a thinly veiled satire to promote the benefits of Populism or monetary reform. Let’s unpack the symbolism.

Oz Characters and Symbolic Representation

Baum’s skill as a writer lies in his ability to create an evocative landscape with parallel allegories, both political and the personal. The political metaphor is obvious. The personal is more nuanced and compelling to the audience.

DOROTHY GALE:

Political Symbolism – Dorothy Gale represents American values and the individual citizen.

Personal Symbolism – Dorothy Gale is the every girl. She is the dreamer. The optimist. The leader of her troupe and the hero on her journey of realization. She is the nucleus of the group, much like Matilda was in her own family.

Journey in Oz: In search of home, self.

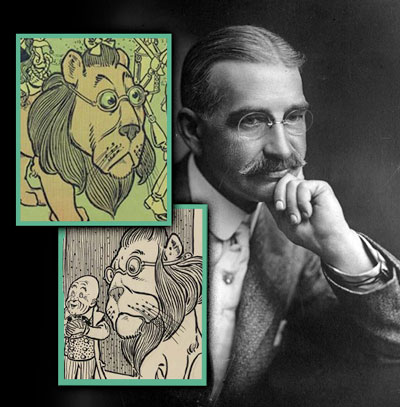

L Frank Baum with cowardly lion character inset.

SCARECROW:

Political Symbolism – The Scarecrow is the Midwestern American farmer. He is wise, but naive and at the mercy of three uncontrollable elements: the environment, economy, and the government. A brain or smarts would help him deal with all three.

Personal Symbolism – The Scarecrow is a good-natured, but gullible chap that’s always getting the stuffing knocked out of him. He’s like a tumbleweed on a desolate prairie. Someone that stumbles through life much like Baum did during a series of early career failures.

Journey in Oz: In search of a brain.

TIN WOODMAN:

Political Symbolism – The Tin Woodman is the dehumanized American industrial steel worker. The steel workers who protested during the deadly 1892 Homestead labor strike at the Andrew Carnegie owned steel mill near Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania were a likely source of inspiration for the Tin Woodman character.

Personal Symbolism – The Tin Woodman is an average working Joe. Baum, likely found inspiration for this character in his own financial struggles and early career jumping.

Journey in Oz: In in search of a heart.

Similarities between the bespectacled Baum and Denslow’s Cowardly Lion illustration are compelling. Could the Cowardly Lion be Baum himself?

COWARDLY LION:

Political Symbolism – The Cowardly Lion is the blustery politician and orator, William Jennings Bryan. During the late 1800s elections, Bryan was the Populist Democratic presidential candidate. His platform promoted the free silver monetary standard over the gold standard .

Personal Symbolism – The Cowardly Lion represents the inner child or self. The courage seeking Cowardly Lion is the character that most closely represents Baum in the book. Compare W. W. Denslow’s original Cowardly Lion illustrations to photos of Baum at the time. There is an uncanny resemblance between the bespectacled Baum and Denslow’s spectacle wearing Cowardly Lion illustrations.

Journey in Oz: In search of courage.

The Wonderful Wizard of Oz characters: Scarecrow, Tin Woodman, Dorothy, Wizard, Toto, Cowardly Lion.

WIZARD OF OZ:

Political Symbolism – The Wizard represents political leaders, particularly any of the US presidents during the late 19th Century. Some historians believe ‘OZ’ stands for an abbreviation of the weight measure, ‘ounce’. This gives more credence to the Populist silver vs. gold monetary metaphor. Baum once claimed that ‘OZ’ was simply taken from the O-Z label of a filing cabinet in his office.

Personal Symbolism – The Wizard is as historian Littlefield aptly describes, “a little bumbling old man, hiding behind a facade of paper mache and noise, …able to be everything to everybody.” He represents anyone who is a fraud, perhaps even Baum. Who at his lowest point in his career may have seen himself as fraud.

Journey in Oz: The Wizard is not on a transformational journey. He is in essence dismantled and revealed for who and what he is, a fraud.

WICKED WITCH (OF THE WEST, EAST):

Political Symbolism – The Wicked Witch of the West in the movie adaptation, represents the American West or more specifically a malevolent Mother Nature, who is eradicated by the farmers’ most precious resource, water. The Wicked Witch can also be interpreted as representing, politicians, government and the corporate ruling class. The Wicked Witch of the East “…has held all the Munchkins in bondage for many years, making them slave for her night and day.”

Personal Symbolism – The Wicked Witch represents maligned minorities who are painted as evil by some – these would be suffragist women and American Indians. The Wicked Witch can also be seen as an illusion or ‘fraud’ that disappears when water is thrown on her visage. It is interesting to note that not all witches in Oz are bad. The Witches of the East and West are seen as malevolent, but Glinda presents herself as good even though her motives are questionable, as she never tells Dorothy that all she needs are the ruby (silver) slippers and her two feet to take her home.

MUNCHKINS:

Political Symbolism – The Munchkins represent ordinary citizens, or the common folk.

Personal Symbolism – The Munchkins also represent the marginalized, or “the little people” which includes all the poor, itinerant workers, European immigrants, Indians, Asian, black and brown peoples.

WINGED MONKEYS:

Political Symbolism – The Winged Monkeys are thought to represent Native Americans or Asian railroad workers exploited by the Wicked Witch of the West. (The East and West symbolizes politicians, government and the corporate ruling class)

Personal Symbolism – The Winged Monkeys also represent all marginalized workers whose unique skills and sheer numbers are exploited in dangerous engagement and conflict.

YELLOW BRICK ROAD:

Political Symbolism – The Yellow Brick Road represents the gold monetary standard, with each brick of gold leading to the Emerald City.

Personal Symbolism – The Yellow Brick Road, in Baum’s theosophical mindset, also likely represents the path to enlightenment and transformation.

EMERALD CITY:

Political Symbolism – The Emerald City represents Washington, D.C., a capitol, or the seat of power.

Personal Symbolism – The Emerald City was for Baum, an entrepreneur, salesman, shopkeeper and publisher of a shop window trends magazine, a magical and shining metropolis of the future. He saw the future with its mechanical inventions and technological advances as a welcoming and wondrous place, much like the Emerald City.

SILVER (RUBY) SHOES:

Political Symbolism – The Silver Shoes are a symbol of silver monetary reform. The Populist movement supported the silver (free money) standard over the gold standard. The Populist silverites were in favor of an inflationary monetary policy using the “free coinage of silver” as opposed to the deflationary gold standard. They believed it would enable debtors (often farmers who had mortgages on their land) to pay their debts off with cheaper, more readily available dollars. Those who would suffer under this policy were the creditors such as banks and landlords.

Personal Symbolism – The Silver Shoes (and Ruby Shoes) are symbolic of power and mobility. They can move you forward in life, or bring you home. The Ruby Red shoes are only found in the movie adaptation. In the original children’s book version, the shoes are silver. The significance of making the shoes ruby red in the movie, may be as simple as exploiting the use of technicolor with a splashy ruby red color. But, it’s likely that the color ‘red’ is a metaphor for the ‘heart’ and this color reinforces the idea that home is where the heart is and “there’s no place like home”.

TORNADO:

Political Symbolism – The Tornado represents political upheaval and the sweeping free silver monetary movement.

Personal Symbolism – The Tornado represents transformational change through transport to another dimension. If you are a theosophist, the other dimension is likely a journey to the center of your mind — perhaps through a dream.

Click Your Heels Three Times

In Oz, the sleepy poppy dust would make us all see symbols in everything and everyone. So with this in mind, perhaps there is some gold and silver political metaphor in Baum’s Oz narrative. And if this is true, surely Matilda Gage has left her sociopolitical imprint on the heart of The Wizard of Oz as well. But, perhaps it would be best to leave the final word on interpretation to L. Frank Baum, who explained his inspiration and motivations for creating The Wonderful Wizard of Oz as this:

In an inscription to his sister Mary Louise Brewster in a copy of his first children’s book, Mother Goose in Prose, more than two decades before his death on May 6, 1919, Baum wrote: